Tackling the Pony Express Trail: A Story of Perseverance

Arrival and Conditioning for a Two-Day Ride on the Pony Express Trail, Part of the Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run

by David K. Lyle

In April 1994, I flew out to Cool, California to go horseback riding in the American River Wilderness area. The ranch I had made arrangements with was the Phase II Sport Horse training facility owned and operated by Patty Bailey. This ranch was the home to Remington Steele, World Champion Arabian stallion. Horses for sale here range in price from $3 million to $100,000. I wasn’t interested in breeding or buying any of the horses; I was there to ride a famous trail. Phase II charges experienced riders $250 for the opportunity to take on the ride of their life through some really challenging terrain and in return, the riders help to condition one of Patty Bailey's horses for a big race in August.

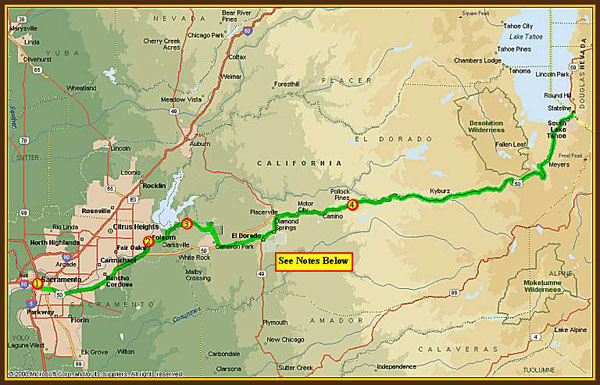

People from all over the world send their horses here to be conditioned for one year prior to running in the Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run. The race runs from Lake Tahoe, California to Cool, California down the original Pony Express Trail that went from San Francisco to Reno, Nevada. This is also the area where gold was discovered in 1849 starting the California Gold Rush. On our ride we would pass some of the old mines, the openings marked by piles of rock called mine tailings. Every August during the full moon, riders run their horses down this trail trying to cover 100 miles in 24 hours. It is a brutal ride and if horse and rider aren’t in top physical condition, neither will make it. For me, an amputee with a prosthetic ankle, the ride would be even more of a challenge.

I wasn't planning to make the ride in 24 hours; my goal was two days. The horses we were riding were still being conditioned and weren’t quite ready for a race pace ride and neither was I.

I spent the first day at the ranch, riding with Patty and one of the trainers in the forest area next to the ranch, getting used to riding up and down the steep hills and learning the temperament of the horse I planned to ride. There would be lots of fun to be had in a beautiful place.

The second day we loaded the horses in a trailer and hauled them about 35 miles northeast of Cool, bordering the wilderness canyon. From there we rode into the canyon with the goal to ride all the back down the American River Canyon trail by nightfall, so we didn’t pack a tent, flashlight, or sleeping bags. This would be the last test. Patty wanted to make sure I could ride before taking on the race.

Most of the trail consists of steep inclines and is only wide enough for one horse at a time. Both sides of the trail were death defying. If the horse fell to the left, you and the horse would fall and roll for 1,000 feet before stopping and the climb back up was usually too steep to access. Bottom line: if you met something on the trail that you didn’t want to meet, there was no escape. As we were in a wilderness area in California, we weren’t allowed to carry guns to protect ourselves from roaming bears and mountain lions. As we rode, Patty kept pointing out the sightings of bear and mountain lion droppings along the trail. She told me of a couple of times that horses had fallen or jumped down the cliffs after being spooked by bears or lions. I had never seen a wild mountain lion outside of a zoo.

Arabian Horses on California Trails: the Ride and the Rush

In order to cover the 35 miles per day, we needed to run the horses at a controlled trot all day. I discovered that a trotting pace is not a good riding position for me because you have to stand with bent knees and support yourself against the horse with your shins. I was having a hard time with it due to the rigidity of my prosthesis, after a couple of hours my leg was killing me. We would stop about every two hours to check the horse’s heart rate and that would give me a chance to adjust my leg.

Close to the end of the day, we approached the north bank of the American River; according to Patty, we were running late. We would have to swim the river and ride hard and fast to clear the boundary of the wilderness area by nightfall. Arabian horses, by nature of their breed, don’t like water; so getting one to swim a swift moving wide river (approximately 100 yards) was not an easy task.

For thousands of years, the Arab horse was bred to be fast, sleek, and hardy so as to endure the heat, lack of water, and rigors of desert battle. When Arab breeders culled their herd for stock, one of the criteria was to deprive the horse of water for three days and then lead the horse to water. If the horse drank the water before being told to do so, the horse was culled from (killed off) the herd. The moral being that water in the desert is scarce, and the master drinks first. The surviving Arab breed today will not touch water unless granted and usually they need to be forced.

We walked the horses up to the ledge next to the river so they could see what we wanted them to do. The adrenaline rush was the most intense I've ever had. We could feel the horses getting tense and jumpy; they knew we were going to run them over the edge. We turned them around and walked back about 50 feet, so we could get a good run at it.

The ledge was about ten feet above the water, but it seemed a lot higher as my horse ran and lunged over the edge. As soon as we hit the water, we moved to either side of the horse where we swam on our own alongside of them. We made sure to keep a slight distance to avoid being kicked. As the water got shallow, we edged closer to the horses' backs, drifting over top of them to remount and ride out of the currents. The water was ice cold and exhilerating-- one of the best times of my life.

When we reached the other side, the canyon wall was very steep and the sun was setting on us fast. Patty was getting concerned that we would have to ride through the woods for the last ten miles in the dark. I told her that riding in the dark didn’t bother me; but soon thereafter learned that her concern was not the darkness but the possibility of encountering night feeding bears along the way. To get to the trail, we had to climb a 30-foot wall at a 50° incline that was mostly rocky surface. Patty wanted to lead so as to show me the way.

The Pony Express Adventure Takes a Turn for Disaster...

As her horse got to the top, the rear hooves slipped and the horse fell. Half rolling, it miraculously landed on its hooves, barely missing me. My horse and I just stood flat-footed, watching as the horse and rider came tumbling down on top of us. Patty fell off in mid air landing on a huge boulder. Her leg broke at the femur bone (thigh); but all told, she was lucky that she didn’t hit her head or she could have been killed. The ranch hand that was riding with us picked her up and saw that the break was serious; meanwhile, Patty was going into shock from the severe pain. I checked the horse for injuries but it was only shaken up-- literally.

We placed Patty back on the horse and rode to a picnic area and laid her on one of the tables. We decided that the ranch hand should ride to the nearest ranch taking all the horses with him so the bears wouldn’t come around for food in the night. I would stay behind with Patty to protect her make certain she didn't go into shock. Since we didn’t pack any blankets or sleeping gear for an overnight stay, I had to use the sweaty and smelly saddle blankets to keep her warm. The sun had disappeared and we were in the dark, 20 miles from the nearest road or ranch, no flashlight, no food, no water, and no gun for protection in a wilderness area teaming with bears and mountain lions. I couldn’t believe it; Patty had a broken left leg and I was missing half of my right leg: together we made a whole person!

We laid together on the picnic table under the saddle blankets for several hours trying to console one another that everything was going to be okay. Creatures of the night were walking around us all through the night, but we could never see anything. A couple of times I had to get up and throw rocks into the bush because the animal noises sounded louder and more threatening than I was comfortable with. We rationalized that it was probably deer but in reality we were scared shitless that it was a mountain lion. We knew bear hunted the creeks at night, but they are usually pretty noisy. The only good thing we had going for us was the fact that we didn’t have food with us to attract any wild animals.

Close to midnight I heard a helicopter in the distance. Sure enough, a rescue helicopter was shinning its search light using the river path as its guide. I climbed on a big boulder and started waving my shirt in the air hoping that the rescue team would spot me. They circled our area for a while never seeing us and then left. I was frustrated beyond my wits end. I figured we were on our own until daylight and prepared for a night of no sleep, just hoping we would not be faced with taking on a fight with some wild animals.

Two hours later, the helicopter came back and spotted our area. They had to land about a mile away in the nearest clearing. Four guys hiked in to carry Patty out to a truck that had followed the helicopter. I carried the saddle blankets. I asked why they left us earlier. They had to refuel because they had been in the air for four hours searching for us. We returned to the mountain rescue center in Cool, where an ambulance was waiting for Patty and I went back to her ranch to inform her anxiously awaiting family members. I told them how freaked out we'd been thinking the mountain lions were going to get us. Everybody laughed, insisting mountain lions don’t eat people.

I said goodbye and boarded a plane to Tucson, Arizona to meet my parents on vacation and go look at some breeding stock at a ranch in Sonoita, Arizona.

Riders Reminded of their Good Fortune on the American River Canyon Trail

One week later, Patty sent me a letter with a picture of a huge bear that they shot outside their horse barn and a newspaper article detailing how a mountain lion had killed a lone runner at the very spot where we waited for our rescue. This was definitely a horse ride adventure to remember.

“ In April 1994, Barbara Schoener, age 40, was attacked and killed by a mountain lion while jogging alone on a path in a wilderness area, El Dorado County, about 45 miles northeast of Sacramento. Barbara Schoener was killed by an 80-pound female mountain lion in Northern California on the American River Canyon trail in the Auburn State Recreation Area. The lion knocked her down a slope and she was badly wounded, but she fought the animal with her arms before she was killed. Then the lion dragged her farther before eating most of her body. “

The accounts in the newspaper said that investigators theorize that the lion surprised her by sneaking within 20' behind her on the tight trail and then ambushing Schoener, knocking her 30' down an 80° slope. The trail is part of the Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run trail. Barbara was the first person in California in the 20th Century to die from a mountain lion attack.

I guess we were lucky.

Author Bio: David K. Lyle is from The Woodlands, TX and is self-described as a “hillbilly by birth, engineer by profession, and amputee by circumstance.” He is a man afflicted by wanderlust who refuses to let his prosthetic ankle prohibit him from traveling to some of the world’s most interesting places. He has developed his own titanium prosthetic components, called the Adaptive Sports Transition Ankle, to better facilitate his travel adventures.