“Breaking” The Cowboy Myth- Cattle Drive History

For many, the cowboy is the cornerstone of American values, representing independence, a strong work ethic, adventure, and courage. But what exactly did a cowboy do on those historic cattle drives?

Cattle driving was the cowboy’s calling. These legnthy cattle drives north began in the state known, even today, as a wild frontier: Texas.

Cattle drive in Colorado

The heyday of American cattle drives lasted from 1866 to 1890, though the first recorded large cattle drive is thought to have occurred in 1846, when Edward Piper drove 1,000 cattle from Texas to Ohio.

Cowboys and cattle would usually begin their journey in the spring months, bypassing the treacherous wintertime conditions and ensuring enough grass for the cows to make the trip. With a herd of 3000 cows, there were might be ten cowboys. A single drive could take two months or more depending on how much terrain was crossed, which made for lots of meals for the cook.

All American cowboy.

The wranglers were responsible for keeping track of the crew’s horses. The process of cattle driving was rugged, but not a spontaneous mission. There was a system of organization to ensure the safe passage of cattle on drives of as many as 2,000 miles. The migrating cowboys worked often in pairs, tag-teaming either side of the herd. Pointers were the front men; the flank and swing men positioned themselves alongside the body of the herd; while the drag men kept any straggler cows from breaking away from the line. These men spread themselves out over the one or two mile expanse and communicated with one another through hand signals and waves of their wide-brimmed hats.

From the Texas plains to Canadian mountains to California shores and Virginia pines—why did the vagabond cowboy go?

Popular opinion regards the cowboy as a symbol of the explorative, adventuresome, and amblin’ American spirit. However, the cattle drive was more in chase of a profit.

Cattle were introduced to the Texas frontier in the mid-1700s by Spanish conquistadors—explorers eager to settle the wild terrain. Cattle drives to California began intermittently in the 1850s because cowhide and beef were in high demand at a pretty price in West Coast mining camps.

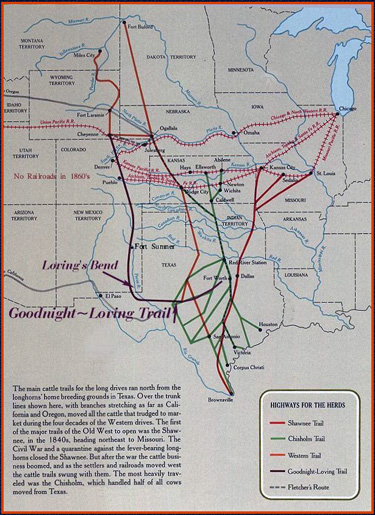

Major trails branching out from Texas

During the Civil War years, from 1961-1965, many cattle drives halted. However, business picked back up again with a vengeance after the war. This period is reflected upon now as the golden age of the cowboy’s cattle drives.

“Where have all the cowboys gone…?”

In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act authorizing the construction of a railroad running from Missouri to California. By the 1880s, the railroad boom, precipitating massive economic and territorial expansions, was well under way. That, coupled with the loss of the vast open ranges, because of overgrazing and drought, caused a sharp decline in the need for long cattle drives.

The cowboy was in less and less demand. Up into the 1940's, he was still charged with herding cattle north to various rail lines on smaller cattle drives, where the cows could then be lugged onto freight cars and shipped to stockyards and packing plants. With the expansion of steel tracks, barbed wire fences and finally the modern cattle truck, those legnthy cattle drives all but disappeared into the sunset.

The trains, signaling economic upturn and the cowboy's downfall.

I once heard a saying “sometimes you eat the bear, sometimes the bear eats you.” The cattle drive has been glorified in myth and culture as an eternal symbol of the American spirit. In reality, it stoked the flame of American industry but when the fire morphed and expanded, it ate the cattle drive alive. Nonetheless, those cattle drives have been enshrined in the collective American consciousness for almost two centuries now.

It is difficult to tell, in an age of vegetarian fads and obsessive dieting, what the future of cattle in this country will be. However, with or without beef, the cowboy and his adventuresome cattle drives will be forever preserved.

Author Bio: Claire Caldwell is a freelance journalist, pursuing a Bachelor's Degree in English Literature and French language at American University in Washington, DC. She is an avid world traveler, having lived in the United States as well as Europe she has also spent time in the Caribbean and Northern Africa. While living in Paris, France, Claire blogged about the differences between linguistic and cultural traditions between America and France as well as about hot-spots and tips for traveling to the City of Lights. She has also worked for the women's travel site, Pink Pangea, blogging about safe ways for women to travel the world independently. She is currently pursuing creative ventures while finishing her degrees.