Sybil Ludington and Her Horse Star, Heroes of the American Revolution

Celebrating “the female Paul Revere” and the horse who carried her 40 miles through a rainy night to gather the local militia and preserve the course of the American Revolutionary War.

by Karen Braschayko

As equestrians today, we often choose to ride based on pleasant weather and enjoying our leisure time with an equine friend. On more than a few rainy days, when I get out of my dry car, opening my umbrella to dash into the warm store, able to call someone via the computer in my pocket if I’m going to be late – I’ve wondered what would it have been like to ride a horse out of necessity on blizzardy days? Would I have been such a fan of riding if it was my only option in the wind, rain and on unlit dirt paths, navigating through near wilderness? Before the days of padded tack and wicking fabrics, would riding have been fun?

Teenager rider Sybil Ludington rode her horse Star more than twice as far as Paul Revere.

I especially wondered this as I learned the story of Sybil Ludington. While we didn’t learn about her via a famous commemorative Henry Wadsworth Longfellow poem as children, Ludington’s ride eclipsed Paul Revere’s ride by doubling it in length, and at 16 she was less than half his age.

Conditions of their rides also contrast. Revere galloped down 14 miles of well-traveled roads through a populated area, it was a moonlit night, he may have stopped for a hot supper, and his ride was done around midnight when he was captured by the British and then released.

Sybil Ludington rode through the night, from about 9 p.m. until dawn. Only part of Sybil’s 40-mile route was on roads, and those were rough roads with dips and holes. We can imagine the spring mud, whipping branches, black wilderness, hilly slopes and narrow paths that forced Ludington to dismount and lead Star through. Familiar landscape can appear mysterious and foreign at night, with landmarks obscured by wind and shiny rain in the moonless dark.

During Ludington’s ride, the woods were also sprinkled with animal predators and outlaws. “Cowboys” were pro-British plunderers, and “skinners” had no allegiance to either army but sometimes dressed in uniform as they stole cattle and terrorized local farmers.

_(14578828258)edited.jpg)

In 1775, Paul Revere's famous midnight ride warned colonial forces of the approaching British troops.

Paul Revere’s horse was borrowed and its true identity slipped into obscurity, but Ludington’s horse Star remains part of her legend. Star was a young horse Sybil trained herself, accounts say, named for the marking on his face as so many horses have been. Sybil’s father rode a big bay Thoroughbred, and after watching Sybil’s skill and passion for horses he gave her a colt, likely locally bred. Sybil loved horses, and she rode daily after her chores were done, preferring her riding time to household duties as many equestrians do.

“Victory or Death! Stories of the American Revolution” says Sybil had a friend named Nodjia, a Native American of the Wappinger tribe who lived in the hills beyond the Ludington’s farm. They tracked animals and explored the woods together.

Sybil was an expert rider, and she and Star were a familiar pair in the region. Sybil had watched her father train the militia at their farm, and she had assisted by running errands and following troops home. She knew where each soldier lived, and she may also have worked as a messenger for the militia.

Horses were pulled from farm duty during the American Revolution, and they were vital contributors to the war. "The Battle of Cowpens," painted by William Ranney in 1845.

Sybil’s father was Colonel Henry Ludington, owner of a successful sawmill, gristmill, and 229-acre farm carved out of fertile wilderness. He and his wife Abigail raised 12 children, and Sybil was the oldest with seven younger siblings at the time of her ride. Their gristmill was built almost entirely by women since men were away in battle at the time. Colonel Ludington took an avid role in local public service, and he was a veteran of the French and Indian War, having enlisted at age 17. Colonel Ludington was a logical choice for militia leader when the American colonies began to fight for independence.

The American Revolution was a local war, with friends and families on opposite sides, spies next door, and battles right in their neighborhoods. Everyday citizens knew what was at stake and aided the war effort in a multitude of ways, and Sybil Ludington was one of these informal soldiers. Colonel Ludington had trained his family on how to protect each other and their home. With a price on her father’s head and frequent threats to his life, there are tales of Sybil preventing his capture, and some say she was his most vigilant protector. Once, she and her siblings scared off potential attackers by marching with guns in front of candlelit windows and making their home seem heavily guarded.

So when a messenger arrived at the Ludington farm on April 26, 1777, too exhausted to travel further, Sybil became the logical choice to ride out and muster the militia. Her father needed to stay at the farm and order the troops as they arrived.

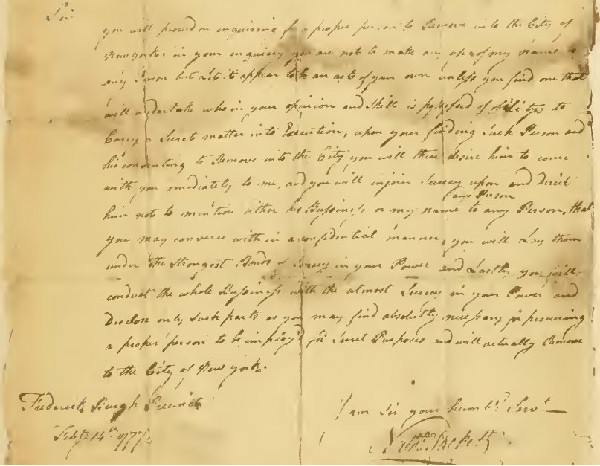

Careful messengers and secrecy were vital during the American Revolutionary War, with spies afoot and interception common. A letter from Nathanael Sackett to Colonel Henry Ludington, 1777.

British General William Tryon had landed off the coast, moving inland unopposed. His 2,000 soldiers reached the town of Danbury, Connecticut, and set fire to private homes and the Continental Army storehouses of meat, flour, rice, molasses, uniforms, shoes and gunpowder, all vital supplies for the colonists’ war effort.

The message that Danbury was burning was an important one. If Tryon’s army continued, they would soon reach the large warehouses at Fredericksburg, potentially crippling the revolutionary movement, or they could attack General George Washington’s army two days away at Peekskill. The militia troops had taken a break from months of battle, returning home to plant their spring crops and scattering across many miles.

Militias of local farmers and their horses were key to the American Revolution. "Veterans of 1776 Returning from the War" by William Tylee Ranney.

So Sybil mounted up, likely with a hemp rope halter and worn saddle, wearing borrowed wool breeches, and riding in her preferred mode of astride. She took off through the dark rain, riding from farm to farm on the 40-mile circuit. She could see the glowing Danbury fires as she passed through Carmel, New York.

Tales differ, but most refer to Sybil carrying a stick both for protection and to knock on doors without dismounting. She may have carried a knife, pistol or rifle. She likely passed marauders who would have harmed her and stolen her horse in a heartbeat, and some versions of the story say she fought off an attack or quietly snuck by campfires in the woods. She would also have known which Tory houses to avoid and which Patriot towns to alert for spreading the word further.

As riders, we can imagine Sybil talking to Star and patting him as she rode, assuring him through the woods populated by deer, owls, wolves, mountain lions and bears. Star may have stumbled on the rough roads, slipped on wet leaves, or struggled through the increasing mud. Sybil’s fingers would have become stiff on the reins as she felt exhaustion and hunger pains through the long, wet night.

When she finally reached home at dawn, nearly 400 militiamen had gathered on the Ludington farm. They immediately marched to Danbury, fewer in number than the British but with surprise on their side. The British may also have been hindered by consuming the colonists’ stores of rum the night before.

This became known as the Battle of Ridgefield. The militia joined with Continental Army troops to drive General Tryon’s army back to their ships, an instrumental day in preserving the course of the American War of Independence.

General George Washington thanked Sybil Ludington for her valiant 40-mile ride. "Washington at Verplanck's Point" by John Trumbull.

Like Paul Revere’s ride, Sybil Ludington’s journey was an inspiration to the troops and the colonists. Later, General George Washington and French General Comte de Rochambeau visited Ludington's Mill to thank Sybil for her all-night ride.

Sybil went on to marry Edmond Ogden, and they ran a tavern and had a son named Henry. After Edmond’s death when Henry was 13, Sybil became the only female licensed innkeeper out of 23 in the Catskill area. Henry became an attorney and followed in the family tradition of public service as an assemblyman.

Sybil had wanted to enlist in the army, accounts say, though as a woman she was unable to formally join. As historian V.T. Dacquino points out in “Sybil Ludington: The Call to Arms,” Sybil was denied a widow’s pension based on her husband’s war service, unable to provide her marriage certificate. However, she was a hero of the American Revolutionary War herself.

Historians have found no contemporaneous records of Ludington’s ride, and many accounts are fictionalized based on the general history of the region and war records. There are several historical records of Sybil Ludington’s life, however, and documents of her father’s contributions to the American Revolution as well.

The tale was passed down by the oral history of Ludington’s family with few public mentions. In 1907, an article about Sybil Ludington appeared in Connecticut Magazine. Soon after, two of Colonel Henry Ludington’s grandchildren wrote a biography about him and included Sybil’s ride.

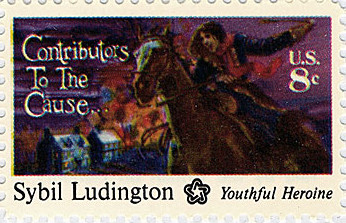

Sybil's war efforts were honored with a commemorative stamp in 1975, almost 200 years after her ride.

Later, Ludington’s ride was revived as part of Revolutionary War commemorations, and Sybil’s efforts were more widely recognized. She was finally celebrated like Paul Revere with two long narrative poems. An opera , a play and a movie have also retold her achievements. Her birthplace of Fredericksburg, New York, renamed itself Ludingtonville in her honor. In 1975, a postage stamp honored Sybil Ludington as one of the “Contributors to the Cause.” In 1963, Congressman Robert R. Barry read into the record a resolution by the National Women’s Party honoring Sybil Ludington’s ride. An annual commemorative road race approximates the route of her night journey.

An equestrian statue honoring Sybil and Star stands in Carmel, New York, along with historical markers mapping the route of their ride. The Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) commissioned the bronze sculpture in 1961, created by Anna Hyatt Huntington. Dramatically, it shows Star as wet and galloping, with Sybil shouting her message and raising her stick. A smaller version of the statue resides at Danbury Public Library.

Sybil Ludington is buried beside her parents at the Patterson Presbyterian Church Cemetery in Patterson, New York. Photo by Anthony22 at the English language Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Before the age of tanks, diesel truck convoys and fighter jets, wars were fought with ordinary horses – backyard-bred, home-trained, pulled from farm work to carry soldiers and supplies for their causes. Star was one of these steeds who did his part on a cold, rainy night to carry his teenage rider and hold the course for American independence. Sybil Ludington could not have gathered the militia without her partner, a brave horse who carried a capable young woman and one of the equine contributors to the American War of Independence.

Explore Sybil’s route at Ludingtonsride.com.

Further reading:

“Sybil Ludington: The Call to Arms” by V. T. Dacquino

“The Horse-Riding Adventure of Sybil Ludington, Revolutionary War Messenger” by Marsha Amstell

“Sybil Ludington’s Midnight Ride” by Marsha Amstel and Ellen Beier

“Glory, Passion, and Principle: The Story of Eight Remarkable Women at the Core of the American Revolution” by Melissa Lukeman Bohrer

“Women Soldiers, Spies, and Patriots of the American Revolution” by Martha Kneib

“Leading Ladies: American Trailblazers” by Kay Bailey Hutchinson

“Victory or Death! Stories of the American Revolution” by Doreen Rappaport or Joan Verniero

“Sybil Ludington: Revolutionary War Rider” by E. F. Abbott

“Ride for Freedom: The Story of Sybil Ludington” by Judy Hominick and Jeanne Spreier

Karen Braschayko is a freelance writer and horse lover who lives in Michigan.